Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, smiles at me and says that she loves Crimea. “In good hands, it could be the most amazing heavenly place.” Oh, yes, of course, this expressive lady in expensive silks and velvet, with a crimson ribbon across her lush chest, is actually an actress dressed as an empress on the occasion of celebrations in honor of the founding of the port city of Sevastopol in 1783 (pronounced Seh-vas- toe-pol). But her feelings are close to what the historical Catherine felt two centuries ago. That Catherine said that Crimea is the most beautiful pearl in her crown.

What is so great about this peninsula the size of Vermont [state in the US], jutting from mainland Ukraine into the Black Sea?

First of all, priroda. Means nature. The Crimean Mountains, which stretch 90 miles along the southern coast, provide protection from cold northerly winds, so that a narrow strip, two to eight miles wide between the sea and picturesque limestone cliffs, enjoys a Mediterranean climate: warm, dry summers and mild winters, with about 250 sunny days of the year.

Not surprisingly, for decades, privileged Russians have come here on vacation – the tsar and aristocrats, then the bosses of the communist party and honored workers, and now post-perestroika speculators and anyone who can afford to enjoy life.

They fill old palaces and relatively recently built sanatoriums, walk in beautiful parks between trees and shrubs from all over the world – cedars, cypresses, sequoias, Chinese palms. The aroma of local Crimean pines, as I was told, is beneficial for your lungs. You just need to get comfortable in a juniper grove, breathe deeply, and all pathogenic bacteria will leave your respiratory system by themselves. People here strongly believe in this and do not like it when they question it.

I arrived here in late spring, when on the infinitely flat interior of Crimea, fields sown with wheat and barley glowed with bright green with scarlet dots of poppies. There are wild flowers along the roads, and when you drive along these roads it is as if you are sniffing honeysuckle or jasmine, as if a tourist bus were smoking them. The birds at 4:15 am sing almost as loudly as the vodka lovers three hours earlier in the hotel next to my room in Yalta, a hotel with 2,500 beds. It dawns by 4:30, and under my balcony beckons the blue Yalta Bay, impressively adjacent to the silvery limestone walls, over which the sharp-toothed peak of Ai-Petri, that is, Mount St. Peter, rises to 4.331 feet.

But I cannot allow myself to surrender to my senses and just enjoy; this Crimean paradise is drowning in problems.

The tourist flow fell by more than a third. Before Mikhail Gorbachev began his reforms in 1987 (“the year when everything began to fall apart,” as one member of the Yalta city council told me), about 7.5 million people annually visited 600 Crimean sanatoriums, hotels, guest houses and tourist camps. … For many people, vacations were subsidized in the form of vouchers from trade unions, factories and organizations such as the Communist Youth Union (Komsomol), which sent children here for free or almost free. Such benefits almost disappeared completely after the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1991. Staying in a subsidized union sanatorium once cost a worker only 10% of his monthly wage; now it is twice his monthly salary, and if he takes his wife and two children with him, it will cost him eight times more than his salary. “So other than that, he can’t buy food, or even buy a sun hat,” complains one Yalta merchant.

Even the number of so-called wild tourists, that is, those who take a tent with them or look for cheap accommodation on their own, has decreased. Why? Inflation. In Ukraine, it is higher than in any other country of the former S.S.S.R. During the time I was there, the price per kilogram of bread jumped sharply from 48 to 100, gasoline – from 750 to 1.300 per liter, and this gasoline still needs to be found.

Prices are given in karbovanets, which are commonly referred to as coupons. This is a temporary Ukrainian currency. When I arrived, the largest bill was 10,000 coupons. Bills of 20,000 coupons soon appeared, and the 50,000th and 100,000th at that time were already in print. A year ago the US dollar was trading at 120 coupons, and now [1993] it costs 3,100. At this rate, the typical monthly salary of 16,000 coupons should have dropped from $ 130 to $ 5. “How can I feed my family,” the woman exclaims, “when a kilo of sausages costs 4,000 coupons?”

Collapse of S.S.S.R. provided Crimea with another problem. Ukraine, declaring its sovereignty, expresses claims to the Black Sea Fleet, based in Sevastopol. The Russian parliament, however, proclaimed Sevastopol a Russian city and the fleet Russian property. Administratively, Crimea was part of the Russian Republic until 1954, when it was transferred to the Ukrainian Republic at the instigation of Nikita Khrushchev. All this was, of course, within the S.S.S.R., so at that time such a transfer meant little.

Ukrainian officials accuse Russian politicians of planning to return back not only Sevastopol, but the entire Crimea, first making it independent and then offering to join Russia. “They want to provoke the Russian population of Crimea,” they tell me. And this is the majority of the 2.7 million Crimeans – 63%; Ukrainians 25%.

Nine percent are Crimean Tatars – a reminder of the peoples who inhabited Crimea before the Russians and Ukrainians; and there is a whole list of such peoples. First, the Cimmerians and the mysterious Taurus, who sacrificed shipwrecked sailors to their virgin goddess. Then the warlike eastern horsemen – the Scythians and Sarmatians – as well as the Greeks who arrived from the south, grew grapes here and exported wheat to Athens and Alexandria. The next came the legionnaires of Imperial Rome, and from the north the Goths. In the Middle Ages, the interior was settled by the Turks, and the Byzantines and Genoese erected trading posts and fortresses on the coast.

In the middle of the 13th century, the troops of Batu Khan and the Golden Horde made the Tatars masters of the entire peninsula, and by the 1500s, the Crimean Khanate, which was in alliance with Turkey, was raiding north to capture slaves and reached Moscow itself. As Russia grew stronger, it expanded southward, and in 1783 captured Crimea. This Russian name comes from the Turkic language spoken by the Tatars – from kirim, which means “fortress”.

During the Second World [Great Patriotic] War, in one night, by order of Stalin, all the Crimean Tatars – 250,000 – were deported east to Central Asia, mainly to Uzbekistan. Stalin accused them of collaborating with the German occupation forces. They say that almost half died on the way and during the first time after settling in a new place. The resettled never gave up hope of returning, and they have been doing so since the late 1980s. Now they are fighting not only ethnic discrimination, but also the economic chaos that has hit Ukraine.

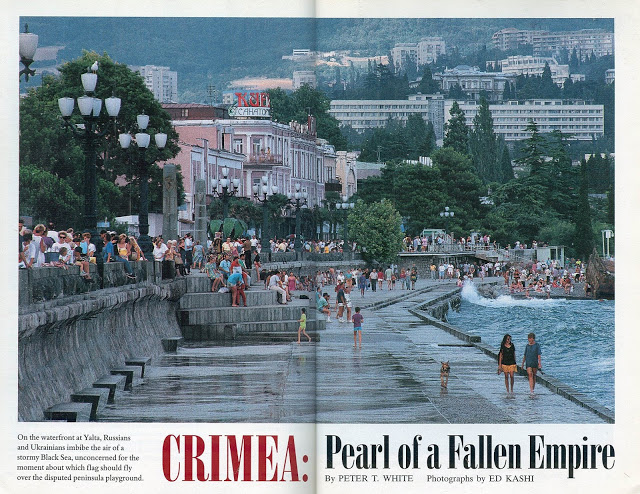

But problems are something that tourists arriving in Crimea do not pay attention to. Yalta is a great place to start. Along the seaside promenade, which is full of entertainment and which still bears the name “Lenin Embankment”, palm trees and roses stretch in a line. People stroll past ice cream stands and souvenir stalls; street artists and photographers offer their services. The excursion boats take passengers on sightseeing walks along the coast of Big Yalta, 50 miles long, which includes a dozen settlements. Today’s economic woes may darken the feeling of luxury a little (my hotel room was obviously rented out for a one-night party while I was away), but Yalta remains the most famous resort in the former Soviet Union.

At the turn of the century, Anton Chekhov kept a house in Yalta, where he painted The Cherry Orchard and Three Sisters; he says this about the newcomers: “Middle-aged women dress here as if they were young girls, and there are a lot of generals around.”

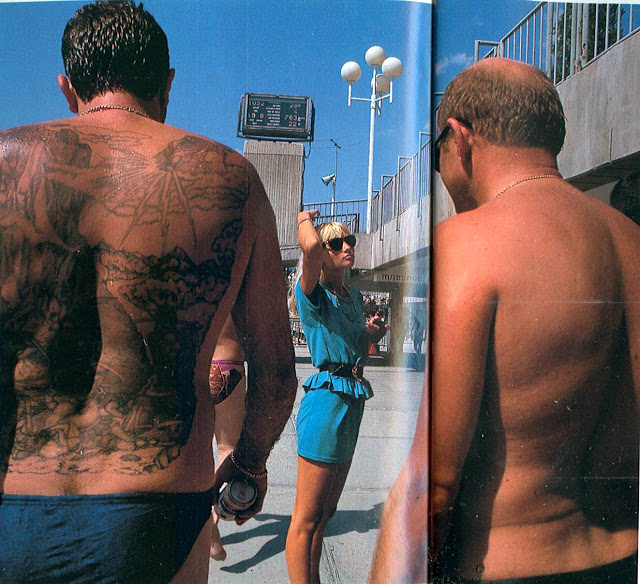

Today he would see young women in super-skinny miniskirts, with brightly painted red lipstick, and quite a lot of bizness. A great place to observe some of the dynamic elements of post-Soviet society is the huge seawater pool at the Yalta-Intourist Hotel. One Ukrainian businessman, who now lives in Canada, but often comes here, explains to me who is who. I will call him Sasha.

A tall, muscular man over there among the stocky, short-haired types – he controls the mafia in Minsk. This lady with two children – her husband is a major businessman in Moscow, he will come for the weekend; maybe he just made another million dollars …

How? “Sale of oil or metals or some chemicals abroad. You buy cheap from government resources, and of course you need a license, so you pay under the table. ” Is it illegal? “Yes, but anything can be done if you have the money and the right connections.”

Sasha talks a lot about the new rich Russians who can afford the Riviera, Mallorca and Miami, but do not feel comfortable there – here they can speak their own language and feel at home. He adds that in Moscow, if you are rich, someone can kill you – a competitor or an envious person, this happens almost every day – so you need to have bodyguards. You can relax in Yalta, but some people come here with bodyguards.

I see these muscular guys drinking on the terrace outside the hotel – short hedgehog haircuts, tracksuits, latest American sneakers. Here, adorable girls in miniskirts are looking for friendship with foreigners, whose wallets are supposed to hold hard currency. (At the next table: she is “One Handrid Dollar”, he is “Let’s go”).

Here I met a Bavarian farmer, a veteran of the German army with a bitter life history. During the war, he was in captivity near Yalta, chopping wood in the mountains. When the guards nearly beat him to death, one woman in charge of the forestry rescued him. After 23 years, he returned and found her, she was then in need, and supported her. He returned many times with groups of German tourists. Now that woman is dead, but he will go to an unfortunate old woman sitting in front of the church and give her as many coupons as she receives in her pension in a few months. “These women are so poor,” he says. “I was told that she has been unable to buy herself a decent piece of meat for two years.”

The word “dacha” in Russian means a suburban area, and it could be a shack with a small vegetable garden, or a real mansion on an elaborate estate, which the leaders of the Communist Party preferred to have on the southern coast of Crimea. Nikita Khrushchev’s dacha near Yalta had one indoor and outdoor cinema, ponds and gurgling fountains, and a bomb shelter at a depth of 250 feet. Sometimes a stranger can get there on an excursion, and I saw an album with photographs of Khrushchev’s guests – Indira Gandhi, Tito, Ho Chi Minh.

Khrushchev’s successor, Leonid Brezhnev, added an indoor swimming pool with sliding glass walls and a cozy bar, where he welcomed important foreigners like President Nixon. Gorbachev stayed here as well, but then he got hold of a vast structure, built further along the coast, near Foros. Now this mansion is closed, but I managed to look at it from the sea, while walking on a tourist boat: a three-story residence with an escalator to the beach, a separate recreational building, rooms for guests, doctors, security. Here in August 1991 the conspirators placed Gorbachev under house arrest; their conspiracy failed after three days, but he himself lost his job four months later.

The most salutary thing on the southern coast of Crimea, as I heard while visiting several of the many local sanatoria, is the very combination of sun, sea air and the fragrance coming from the parks. But treatment is also offered in connection with specific problems: massage, acupuncture, soft music to relieve stress.

Some things are still hard for me to believe. Application of electromagnets for varicose veins? Even pebbles on the beach, I was assured, could have therapeutic effects. Depending on which part of your foot such a naked is pressing on, the nerve pathways to different organs will transmit beneficial stimulation. But these days, says the director of the sanatorium, most people prefer to just relax.

Moored at the Lenin embankment in Yalta, a snow-white ship called Professor Zubov reflects another new reality. It belongs to one Russian scientific institute, but no longer makes research trips, since the institute is experiencing big problems with funding. One private company leases this research vessel for charter flights, and once a week a hundred or more passengers take it to Istanbul, where they buy Turkish goods – rags, chocolate – for cheap dollars to sell here. This is a quick way to double your money and it’s called kupil-prodal.

At the Kirov sanatorium, a dozen men and women sit in an enclosed space where air saturated with the smallest particles of salt is injected [this is called a salt cave]. It helps very well with bronchitis, asthma, sinus problems, says the attendant – 200 coupons per visit (seven cents at a time). This is also a response to the new conditions. The sanatorium, no longer subsidized by the state and needing money to keep from closing, leases this room to one of its doctors, who set up a private firm to raise his too low salary. He says he can’t make much money yet; yet the best thing in our time is kupil-prodal.

Changes have also occurred in the main Yalta attraction – in the large snow-white Livadia Palace, which is a few miles down the road from Yalta. This palace was once the summer residence of Nicholas II, the last Russian tsar. The guides say that before they mentioned him only in passing. The emphasis then was on the fact that in the dining hall, Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt in 1945 met during the Yalta Conference to develop a map of post-war Europe. But now visitors are most intrigued by the recently hung photographs of the imperial family – drinking tea in the park, playing tennis, splashing in the surf. A tourist brochure, sold at a city-owned kiosk for 200 coupons, outside the palace, literally 300 feet away, is now worth 2,000 coupons – kupil-prodal in full bloom.

A highway along the sea leads from Yalta west to Sevastopol, a dignified naval city that has gone through hell twice. For the first time – during the Crimean War of 1854-1856. Ten years after the end of that war, Mark Twain, on his European tour, saw what 349 days of siege and bombing by the British, French, Italians and Turks did in that war against Russian expansion.

Pompeii, Twain says, is relatively well preserved in comparison with Sevastopol. “Wherever you look,” he writes, “everywhere your gaze cannot catch on to anything except ruins, ruins, ruins!”

In the vicinity of Sevastopol, in the middle of the vast vineyards of the state farm “Zolotaya Balka”, there is a white obelisk with an inscription in English: “In memory of those who fell in the Battle of Balaklava on October 25, 1854”. On this day, the Russians captured several British artillery pieces, and the British commander ordered his lancers and dragoons to repulse them; his orders were misunderstood [see below, my note], and the direction in which they were ordered to attack made them vulnerable to Russian artillery fire from heights on both flanks and from the front. 670 men of the light cavalry brigade obeyed the order. This was the very attack in Death Valley that Alfred, Lord Tennyson, immortalized in his poem. Only 195 people returned back.

At the place where the attack drowned, there is now a small village of Khmelnitskoye. When I read a sign on one of the buildings – Primary School No. 36 – there was a deafening b-oo-oo!

What was it? They reassured me. During World War II, Sevastopol and its environs were destroyed again as a result of the 248-day German siege. Unexploded mines and shells are still found and detonated so that they do not cause harm.

Now Sevastopol, painstakingly rebuilt from scratch, is in a state of political uncertainty, filled with dismayed officers and ordinary citizens.

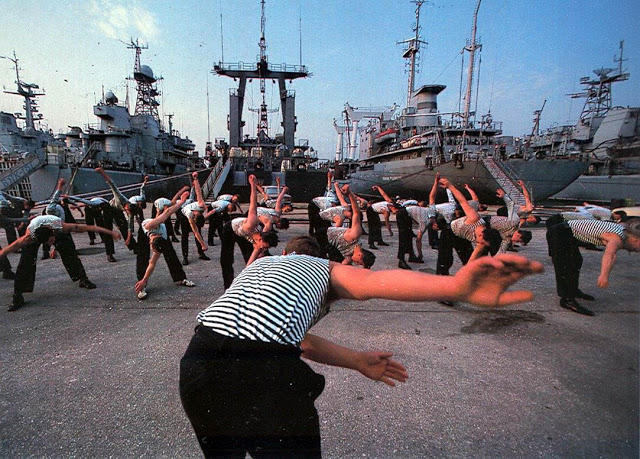

I was impressed by the warships in the bay — the Moskva helicopter carrier, a dozen missile cruisers and anti-submarine frigates. But, as one [Ukrainian] captain tells me, these are, in fact, all the old troughs, their crews are losing their qualifications, because the ships – there are 200 combat ships and 130 auxiliary – rarely go to sea. No fuel, no money.

I go down inside an old diesel submarine of 1965 model. It is necessary to change some parts of it, produced in St. Petersburg, but Russia does not send them, and Ukraine does not have it at all, the lieutenant says. “So we repair ourselves as best we can. In any case, no one understands what is happening to us, do we belong to Russia or do we belong to Ukraine? ”

Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk met frequently and promised to split the fleet 50-50, but nothing happens. Officers give vent to their feelings at rallies. Likewise, civilians who gather for a demonstration in the city square; many of them are pensioners who are stifled by inflation. “This is the city of Russian glory!” “They want to tell us that we have nothing to do with Russia. They want to make our children speak Ukrainian! ” “Leave us alone, Ukraine – we want to be with Russia!”

The Ukrainian captain, surrounded by a crowd, is scared. Russian propaganda works here, he whispers – “People think that they were better off before. They don’t remember bad things. ” The organizer of the rally tells me that he has no doubts that the entire fleet, together with Sevastopol, will leave for Russia, and ultimately the whole Crimea. “The fleet and the police are on our side.” Does he foresee armed clashes? “Only if the Ukrainians start shooting. Then we will answer. ”

The world’s longest trolleybus line stretches 50 miles, linking Yalta to the capital of Crimea, Simferopol (pronounced Sim-feh-roe-pol).

The massive building that was the headquarters of the Crimean branch of the Communist Party is now the Supreme Soviet, that is, the parliament, of the Republic of Crimea. When I visited this place, there was a man inside who was at that time the most influential politician in Crimea, Nikolai Vasilyevich Bagrov, once the first secretary of the party, and later the chairman, or speaker, of parliament. He told me that he had changed a lot.

“Before, there was only one opinion, and it was not questioned. But I learned patience to control myself and listen to the opinions of others. Sometimes these opinions are unreasonable, not constructive, so it is very difficult to listen and find a grain of truth in them. I got myself a headache. ”

After my visit, great changes took place. At the end of January, Bagrov announced his candidacy for a new post – the President of Crimea, and gained 23%. Yuri Aleksandrovich Meshkov won with 73%, promising to separate Crimea from Ukraine and annex it to Russia.

Since then, Meshkov has changed his position: autonomy will be enough, he says now, if it only presupposes freedom in determining economic policy and the right to conclude treaties with foreign states. And he is ready to fulfill his campaign promise and make the Russian ruble legal tender in Crimea again.

No wonder – by January [1994] the Ukrainian coupon had already dropped to 40,000 against the dollar – and it continues to fall …

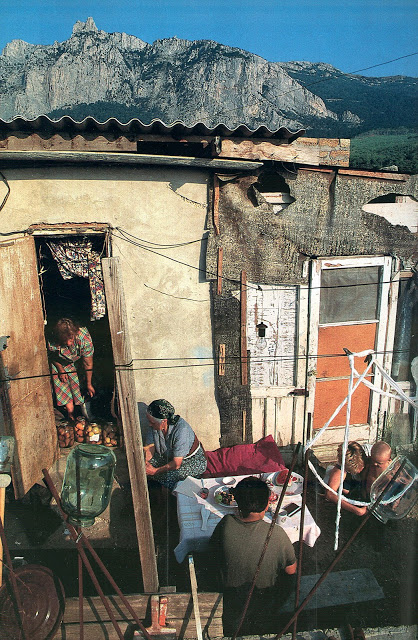

On the hills around Simferopol, spontaneously built up villages are a reminder of the bitter fate of the Crimean Tatars, who have owned this land for over 300 years. For many, as I have seen, new life here is not sugar. There is no electricity, and water is delivered in cisterns and must be carried home in plastic containers. Many tiny houses are unfinished – the money brought with them from Uzbekistan has depreciated, and it is impossible to buy in the required quantity neither blocks of cinder-concrete nor lumber. At least those plots of land on which these houses are located now belong to them; before, in the Soviet state, the police could drive them out of there. Everyone grows fruits and vegetables. “If you have at least five hundred square meters,” one old man tells me, that is, an area of about 60 by 90 feet – “you will never die of hunger.” But you can freeze in winter – coal is so expensive. Many told me that in Uzbekistan they lived in abundance, but everyone says that they are happy to return to their homeland.

The elected leader of the Council [Mejlis] of the Crimean Tatar people, Mustafa Dzhemilev, now 50, was deported when he was only six months old; he later spent 15 years in prison for campaigning for the right of his people to return. “About 250,000 have now returned,” he tells me, “and they keep coming.” No, they do not expect to be returned to their former homes, but persistently seek representation in the Crimean parliament, with a veto on issues concerning the Tatars.

In a conversation with Mustafa Dzhemilev, I recall that I was surprised when I saw that Tatar women are blondes, with blue eyes and rosy cheeks. Mustafa Dzhemilev smiles. This is due to how our people were formed, he says. Tatars-Mongoloids lived in the steppes; in the south, some Greeks, Goths, and Genoese converted to Islam and adopted the Tatar language, thereby becoming Tatars. The steppe Tatars and Primorsky Tatars mixed, so now there is no longer what could be called a “typical Crimean Tatar face”.

He adds that among his people the knowledge of the Tatar language is weak – for a long time there were no Tatar schools; all were educated in Russian. “We hope to gradually change this, prepare teachers and receive textbooks.”

South of Simferopol, in Bakhchisarai, the last capital of the Crimean Tatars, the khan’s palace of the 18th century is being restored. It is said that over a hundred fountains gushed here. I walk past the Holy Fountain of Paradise, the Fountain of Life, the Lulling Fountain. All of them are dry, except for the one at which crowds of tourists linger – the Fountain of Tears. He gained fame thanks to a poem by Alexander Pushkin, dedicated to the khan’s bitter sorrow over the death of the beautiful Polish princess, a concubine from his harem. Several Tatars in white skullcaps enter the nearby palace mosque for Friday prayers to be performed by an imam from Turkey.

What is along the western coast of Crimea? The small town of Saki, where they offer treatment for rheumatism with healing mud, as well as the industrial city of Evpatoria with a dozen children’s sanatoriums. The pastures with cows and sheep that stretch along the road alternate with wheat fields and cherry, apple and peach orchards. On a gentle hill near the village of Novoozernoye, I see steel towers 60 feet high with 28-foot blades spinning at the tops of these towers – three windmills. “Protected by US Patent 4,426,192,” the plaque reads. This is a pilot project for a joint venture: the mechanical structure is made in Ukraine, the technology is from a San Francisco firm that has built a successful wind power system in central California. [The project was implemented according to the program of L. D. Kuchma, but the indicated wind turbines at that time were already outdated.]. Winds are constantly blowing in this region, and designers see 5,000 wind turbines with a capacity of 500 megawatts in the future. If these dreams were realized, then one of the largest wind energy parks in the world would appear here. But will this project be implemented?

Not far from the northwestern corner of the peninsula, I see tugs pulling barges from the port of Chornomorsk to service offshore gas rigs. Earlier in these places a fishing group called “Tavrida” caught herring and flounder, and also preserved shark liver paste. The fishing industry is now in decline due to overfishing and pollution of the sea, so the collective is now forced to look for other ways to make money: growing nutria for fur and caring for 750 acres of lavender and wormwood, from which cosmetic oil is made. The chairman tells me that a year ago he signed the joint venture documents with an after-shave lotion company in Corpus Christi, Texas. “And we sent them samples of our oil,” he says, “but still there is no answer …”

The hot summer season is here – it’s a good time to spend a pleasant day in the mountains, in the Crimean State Nature Reserve. Its 85,000 acres once served as hunting ground for the kings. Vladimir Lupsha, who has worked here as a forester for 29 years, leads me along a narrow road through alternating zones of oak, beech and then pine. 4,000 feet away is a large meadow with white and pale pink spots of daisies and tiny wild roses. The bald eagle is circling over our heads.

On the way, we stop for a bite to eat, sitting by the stream – in the favorite place of Leonid Brezhnev, who came here even when he was so decrepit that he could not shoot without leaning against a tree. Here, as Vladimir Lupsha says, wild boars, gazelles, mountain sheep are found. And thousands of wild deer. Among them there are such majestic beauties who reach eight feet when you count to the top of their horns. But since 1987, no one has hunted here. There are no walking tours; it worries animals. But outside the reserve, in the rest of the Crimean Mountains, there is 20 times more space where you can go hiking and camp. Adventurers can climb down the Grand Canyon, a narrow valley with steep slopes, descending a thousand feet. And there, plunge into a pond of ice water, known as the “bath of youth”.

That night the full moon cast a shimmering silver path across the truly black Black Sea …

To catch a glimpse of the rest of Crimea, I head northeast of Yalta along the road along the coast, which winds in a serpentine like an endless snake, now rising up and running down, between green vineyards and gray pebble beaches along the turquoise and emerald sea. In Sudak, five towers of the Genoese Fortress appear from behind the coastal hill. The fortifications in Feodosia are Byzantine. Here, in Feodosia, is the end of the Crimean Mountains; from here to the Kerch Strait, which connects the Black Sea with the Azov Sea, wheat ripens and cattle graze everywhere. Kerch, a railway station and the main Crimean commercial port, has become a transit point for export goods coming from many new countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, after since they opened to foreigners two years ago. “In 1992, we received 186 ships,” says one municipal official. In 1993, their number doubled; here they are loaded with coal for Italy, steel wire for China.

Kerch is also a home port for fishing vessels that catch fish in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean, canned it and sell it abroad for hard currency. And the Zaliv shipyard – where the first Soviet cargo ship with a nuclear power plant was built – has now switched to the production of double-hull tankers in a joint venture with Pepsi-Cola; in the future, perhaps they will retrain for pizza and work for Pizza Huts.

And further. Kerch is a real treasury of ancient values. “Wherever you stick a shovel, you will definitely find something historical,” says the director of the Kerch Museum of History and Culture [meaning the East Crimean Historical and Cultural Museum-Reserve]. He mentions thousands of burial mounds in the vicinity, some of which are 2,500 years old. Archaeological excavations have resulted in the treasures of the Greek colonists and their Bosporus kingdom, as well as elegant Scythian gold jewelry, now kept in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. Some of the mounds have yet to be discovered, and I heard archaeologists from Montreal and Brigham Young University, Utah are waiting here. Is it any surprise that these burial mounds also attract robbers in Mercedes and machine guns when a coin found here could bring in $ 25,000 in revenue?

I drive westward along the flat, dry, fertile steppe, which occupies almost two-thirds of the entire Crimea, and then follow along a canal reinforced with concrete walls northward to the city of Dzhankoy, to Pumping Station No. 1. Water comes here from the Dnieper, through The Perekop isthmus connecting the peninsula with the Ukrainian mainland. Until this point, the water flows by gravity, says the station manager. Its pumps lift water about 30 feet [9.5 m] so that it then fills a network of canals and pipes that irrigate 1,500 square miles from April to November with wheat, barley, orchards, vineyards, and sunflower fields. This is the lifeblood, the circulatory system of Crimean agriculture. Before, up to the 1950s, “everything was like in the desert,” they tell me. “The people had camels.”

But water is not everything. On a collective farm where five harvesters are harvesting wheat, I hear that the harvest is good, but two-thirds of the proceeds will go to fuel. The Mir flower farm in the village of Yantarnoye sends a million tulips to Moscow and Kiev at the beginning of each year, but its numerous greenhouses will simply cease to function in the absence of fuel for heating.

If mainland Ukraine supplies Crimea with water in excess, it supplies it with petrol and oil in extremely insufficient quantities, since all this must come from Russia, and Ukraine has no money.

In fact, Ukraine is heavily indebted – reportedly the equivalent of $ 2.5 billion, or even more – and at times Russia threatens to cut off fuel supplies altogether. In September 1993, Presidents Kravchuk and Yeltsin met again in one of the former grand ducal palaces near Yalta [we are talking about the Massandra Palace] and announced a new agreement: in order to pay part of its debt, Ukraine will yield to Russia’s demand to have a share in the Black Sea Fleet!

But when Kravchuk returned to the capital, Ukrainian parliamentarians said they would never ratify the deal. After that, another agreement was reached: Ukraine receives 15% of the fleet and a loan at 35 percent [?]; The Sevastopol naval base should be leased to Russia. But ratification is still in question. So huge economic and political problems remain unresolved, and the Ukrainian coupon continues to fall lower and lower. The outlook is bleak and uncertain.

However, Crimea possesses such a product, for which, as it seems, there will always be consumers – and this product is priroda. In the spring, these are fields covered with poppies, just at the time when it is snowing in Moscow. In summer, these are Black Sea beaches and beneficial forest ethers, when the temperature of the sea water and the air temperature are the same. And in autumn, this is the charm of the southern coast, when the atmosphere is clear as crystal, and the colors of the sea and sky are unusually bright. Deciduous trees among evergreens turn yellow, crimson, and also red; the vineyards glow with purple and gold. People say that light breezes caress you – it feels like you are floating. They call it barkhatnyy sezon. That is why Crimea must look ahead and hope for the best, in spite of everything.